An Interview with Gregor Radonjič: METAPHORICAL AND METAPHYSICAL SPACES

(Gregor Radonjič & Alexandra Wesche February 27, 2022)

Finding this interview with Gregor Radonjic led me to an exploration of his work as his motivation for photographing resonates with my own at this time, he says that he is “deeply interested in photography which moves our spirits closer to the silent places beyond what is meant by ‘real” (Wesche, 2022), and that he relies on Alfred Stieglitz’s concept of “equivalency”, where images were intended to be interpreted as metaphors for emotional states. Radonjič comments on the work of Minor White, where symbols in images forms a metaphor for something beyond the subject being photographed, as he also believes that an image can be a transformation as well as a document, and that they should be open to individual interpretations.

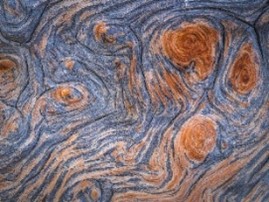

Like myself Radonjič is interested in tree-related photography, believing that photographing trees and forests is a serious artwork.One of hisprojects is dedicated to trees and is published as a book ‘Drevesa’ (trees in Slovenian). In the introduction he refers to trees as social beings, as well as individual characters and to the ancient connection that humans have with them. I was interested that Radonjič says that photographs of trees can add to this hidden connection between humans and trees. He describes the liberating feeling of being in a forest where you are all alone without any distractions as well as being attracted to the “visually intertwined living space” (Wesche, 2022); this is something that I feel strongly. He also describes forests as very visually chaotic and complex as place. His photo book combines poetry and images which he considers synergetic.

(Radonjič, Trees 2016)

His work Metascapes is about transformation and representing what is in our subconscious. He explains it as transforming places into personal ‘mindscapes’ which reflect his intimate inner relationship with those places. Radonjič describes his images as a mental projection of how we perceive our surroundings, that they “function as “distorted” mirror of the reality we see. They are not pure documentations, but rather artworks somewhere between fiction and abstraction, metaphors of an outlook on the world and beyond” (Radonjič, 2016). On landscapes he quotes the anthropologist Orvar Lofgren“The real landscape is in your head.” Radonjič describeslandscapes as spatially based perceptual units, constructed in our minds as we view the world by means of “aesthetic categories that are socially mediated” (Radonjič, 2016).

You can see in his work Metascapes to achieve this he uses creative intervention in post-production.

He considers colour a very important element in visual art and comments that he uses colours to communicate his vision to the viewers. However, he doesn’t adhere to right or true colours, and this is evident in his work. He explains that he uses postproduction techniques to “transfer inner feelings and memory to photographs”, as he knows what he was experiencing at the moment he pressed the shutter, and using digital tools makes it easier and more effective for me to convey these inner feelings”. He does also point out that using analogue techniques is also a manipulation of reality and believes that using them is another part of a creative path.

My reflections:

His photographic style and final output, particularly his use of post-production work doesn’t particularly appeal to be, but his photographic philosophy does. I sympathise with his ideas on equivalence, metaphor for something beyond the subject being photographed, that there should be room for interpretation by viewers and note his idea that photography can be a transformation as well as a document. His description of place being transformed into personal ‘mindscapes’, that reflect his intimate relationship with those places is part of what I am trying to achieve, but I am also sharing something beyond the forest.

The fact that he enjoys working in forests undistracted and is attuned to Trees as connecting to humans aligns with my practice. His ideas on forests being visually chaotic, is exactly what I am seeking to show in my BOW assignment 3.

I will consider his comments on not using true colour and may see where that takes me sometime in the future.

Overall, I completely concur with his view that the real landscape is in one’s head.

References:

Radonjič, G. (2015) Trees At: https://gregorradonjic.wordpress.com/portfolio/places-perspectives/ (Accessed 31/08/2022).

Radonjič, G. (2016) Metascapes. At: https://gregorradonjic.wordpress.com/metascapes/ (Accessed 30/08/2022).

Wesche, A. (2022) ‘An Interview with Gregor Radonjič’ In: On Landscape (250). Ed. Tim Parkin. pp.97–118. Found at: https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2022/02/interview-with-gregor-radonjic/ [accessed 30.7.22)

GUY TAL: COLOUR AS FORM

This article interested me as I have recently made the decision to shoot in colour for the rest of this project. Tal outlines the history of colour in photography and I was interested to learn that in 1946 about a decade after releasing colour film Kodak commissioned photographers, including Paul Weston, to use colour for an advertising campaign. Apparently, Weston was surprised that he enjoyed shooting in colour and maybe only didn’t produce much more in colour, as he was at the end of his photographic career by that stage.

Tal explains that Edward Weston understood that black and white and colour were not interchangeable and a deliberate choice was needed depending on subject and form. Weston suggested colour is needed when it separates the objects in the composition more so than other elements like tone, shape, pattern, or texture; and believed the mistake was in not thinking of colour as form. I hadn’t realised that Weston’s son Cole was a pioneering colour photographer, who said “to see colour as form means looking at the image in a new way, trying to free oneself from absorption in subject matter” (Tal,2022:45).

Tal speaks of colour as a means of subjective expression, and interestingly for my work in Contextual Studies the importance of subjective expression over objective representation if artistic expression is an artist’s goal (Tal, 2022:47). He points out that unfortunately some think that the use of colour may attract viewers attention, instead of skillful composition.

Interestingly like Radonjič , he explains that photographer’s do not have to remain true to colour, just as black and white photographers don’t, as colour can be controlled just as tonality can “many photographers consider colour as something to reproduce rather than as something to control and to use expressively” and suggests that “A good way to think about artistic expression in photography is as the act of creating and using form consciously and expressively” (Tal, 2022:47).

Tal suggests form may be:

- Rendering 3-d objects onto a 2-d surface using lines, tonality, tonality and colour to create the perception of depth.

- Form as composition of the meaning inferred from an image, combining visual elements so they express the visual elements to express the artists meaning.

He ends with a quote from Ernst Haas, “The camera only facilitates the taking. The photographer must do the giving in order to transform and transcend ordinary reality. The problem is to transform without deforming.” (Tal, 2022:55).

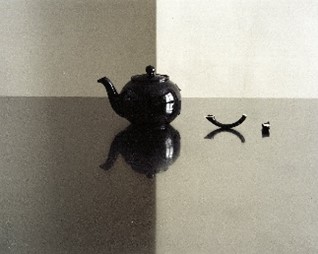

(Tal, 2022)

My reflections:

It is interesting that like Radonjič doesn’t believe that it is important to retain true colour and that it can be used for subjective expression – I should definitely consider this. He also mentions transforming; I like his challenge to transform without distorting.

Reference:

Tal, G. (2022) ‘Colour as Form: Transforming without deforming’ In: On Landscape 254 pp.41–66. Ed. Parkin T. Found at: https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2022/04/colour-as-form/ [accessed 27.8.22]

TUTOR SUGGESTED RESEARCH/READING

Gilles Peress

In this interview Giles Peress, he talks about text and images and the new meaning that forms beyond the two. It is a conversation between Peress and Gerhard Steidl publisher of his book Whatever you say, say nothing (2021). This book is a response to his time in Northern Ireland in the 1970s, images combined with much contextual material which he calls “documentary fiction”. Peress sees an enormous gap between language and reality. These are the points that I found most interesting:

- Perez makes books to process possible traumas and relationship to everything, in the book for him “everything happens”.

- He says he is suspicious of attempts to construct definitive documentary or “stable truths”.

- He explains that the title is the essence of a book as it is the Gestalt of the idea (an organized whole that is perceived as more than the sum of its parts) and leads to what it can become- it gives you a clear vision of what you are doing. So, you should continually refer back to the title; I do this when writing, but do I do it always when shooting?

- He describes how when he sees something that slows down the narrative in the book that he “kills” it. This is good advice.

- He says that there are many voices in a book, primarily, reality, you and the interpreters, so there is a multiplicity of authors in a book.

- Peress suggests that the actual process of making a book, is very important, as photography explores what happens between the moment of perception and the moment of the work, which brings a space in which different ideas take shape.

Reflection: His ideas give some good advice on book making and narrative.

Reference:

Peress, G (2022) DBPFP22: Gilles Peress (s.d.) At: https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/dbpfp22-gilles-peress (Accessed 07/09/2022). At: https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/dbpfp22-gilles-peress (Accessed 07/09/2022).

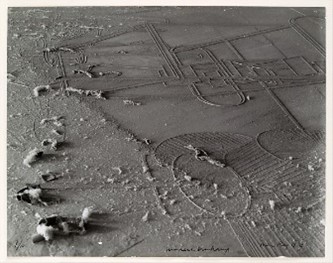

DUST BREEDING MAN RAY (1920)

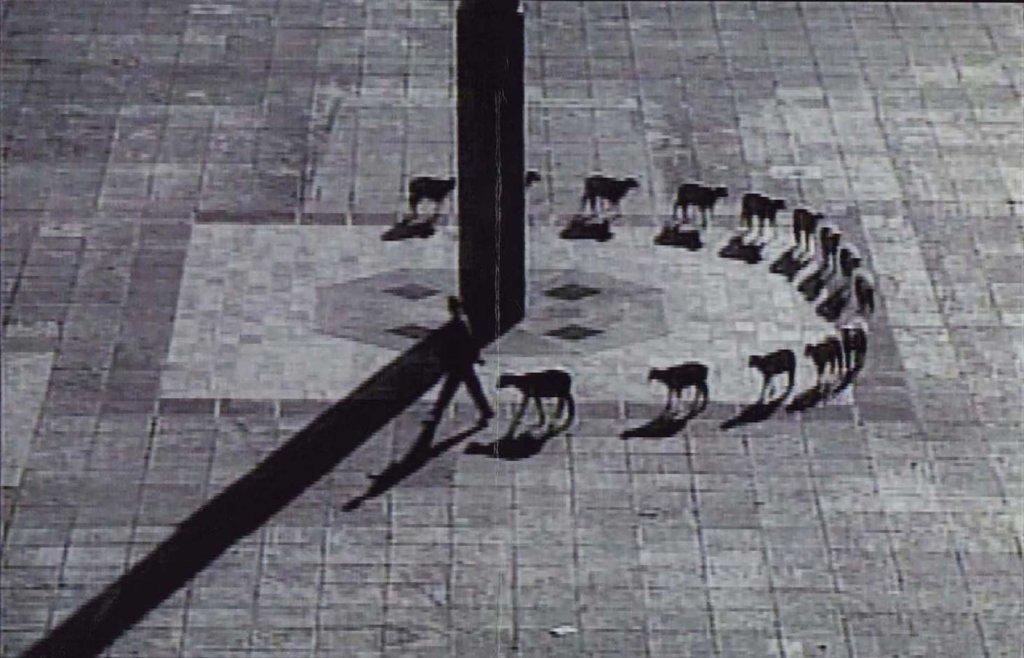

(Man Ray, 1920) (Man Ray, 1929)

Man Ray photographed the large glass sheet in Duchamp’s studio after a years’ worth of dust, using a two-hour exposure to capture the texture and variety of debris on the glass surface. Company tells us that Man Ray cropped the original image down, removing the detail from the contextual details in the background. Company describes it as bearing “little resemblance to the functional photography” and that it was first published in the French surrealist journal Literature, possibly making it the first surrealist photograph (Company, 2005:48).

Man Ray initially titled it “View from an aeroplane,” adding to its ambiguity. As the titles give us information, probably the later title “Dust Breeding” is more informative. Company points put that whether viewed as a macro or micro it looks like a wasteland and his later image Terrain Vague (1929), along with many other images. The subject was eventually set in varnish and sandwiched between glass plates as “The Large Glass.” Apparently, Duchamp wanted it to retain ambiguity with accompanying text as indefinite as possible.

Company sets out that dust is a trace of what was before the camera, and that the photograph can photograph our attention on such transient things. In semiotics this is an “index” a sign caused by its object. He also suggests that a photograph is an index as it is an indication of the presence of a camera.

Ultimately Company uses the image Dust Breeding as an example that photography has two roles in art, as an art form and as and functional way to document and publicise art forms.

I have always been fascinated by this photograph, so it was good to take the opportunity to study it more closely. Most interesting to me is Company pointing out that I can view an image as a macro or a micro, which I’d not thought of.

References:

Man Ray (1920) Dust breeding At: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/271420 (Accessed 07/09/2022).

Campany, D. (2005) ‘Dust Breeding 1920’ In: Howarth, S. (ed.) Singular Images: Essays on Remarkable Photographs. London: Tate Publishing. pp.47–53.

Man Ray. (1929) Terrain vague. At: https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/ressources/oeuvre/cKL8o8 (Accessed 07/09/2022).

INSIDE THE OUTSIDE COLLECTIVE

This is a landscape photography collective who mediate the liminal space between the world before us and within. The founding members are Al Brydon, Joseph Wright, Rob Hudson and Stephen Segasby, the members explore place making personal representations of landscape, expressing their inner selves and their relationship with the land. Their name was taken from a naturalist and founder of the American national parks’ movement John Muir, who said, “I found that going out was really going in.” (Hudson, 2016).

They use a combination of narrative, metaphor, and investigation, believing that “there’s a big difference between a photograph of something and a photograph about something” (Hudson, 2016).

They are both in the landscape and representing the landscape, so inhabiting two worlds, “the one before us and the one inside us. And when those two worlds collide and intermingle the result can often surprise” commenting on the transformative effect of this combination (ITO, 2016). Referring to a 2016 exhibition by the collective, Hudson says the intention of the photographs often is to make the abstract worlds of thoughts and feelings more concrete through the representation of the physical world around us.

I have been particularly inspired by the work of several of the members, which I now detail below.

References:

ITO (2016) Inside The Outside Collective At: https://www.inside-the-outside.com/about/ (Accessed 08/09/2022).

Hudson, R. (2016) Inside the Outside. At: https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2016/10/inside-outside-exhibition-photography/ (Accessed 08/09/2022).

ROB HUDSON

Describes himself as a conceptual landscape photographer who uses metaphor and narrative and is often influenced by poetry. He says that landscapes are dependent on how they are imagined through our “intellect”. In photographing them we are representing a physical reality, what we knew before and what we know after being in the landscape and express something of our inner selves.

Hudson explains two ways that we experience the landscape “One is lived, illiterate and unconscious, the other learned, literate and conscious.” (Hudson, 2016).

Talking about his projects he says he has three premises; they are personal, “restrictive” maybe by subject, area, style and or theme and he is passionate about them. To work he develops a backstory to find what he’s trying to convey so he is not overwhelmed when in the landscape. He also shares that contrastingly images can be the start of informing your ideas, though he generally uses words to generate more clarity and more depth about how he feels and what he wants to represent in a project. His preparation method he outlines is similar to my own:

- Make lists of keywords about my feelings, history, and my associations with the place.

- Look at previous work by others

- make a quick list of images to avoid- this I don’t do but it’s a good tip.

He says this means we produce work that is different, think creatively and look inside ourselves to find a way of expressing our ideas.

Hudson is keen on using series of images to strengthen what a photographer is as this allows viewers to make links and engage their minds. Interestingly he shares that he’s interested in John Berger’s ideas about seeing images in series, “how the force of multiples reinforces the potency of individual images…a series of refrains” (Hudson, 2016). I agree with this.

He also talks of trees saying that trees aren’t in competition with one another, but instead exist in a complex web of interconnecting roots and fungi, exactly as I have talked of. His work ‘The Secret Language of Trees‘ is his search for “visual clues to that connectivity and mutual nurturing” Hudson, 2022). He knows this is not documentary, it is subjective and has multiple layers of visual influences.

The Secret Language of Trees (Hudson, 2022)

His work Mametz Wood, not taken in that actual wood, but based on a poem about the WW1 of the Royal Welch Fusiliers in in the battle of Mametz Wood, a futile fight for just one square mile of woodland in northern France. This was his starting point to explore the effects of war on the mind, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in particular. Here he used double exposures to “both disturb reality and create a strange, surreal landscape that explores the experience of, or what was then known as shell shock”, saying that it is not obvious what is real and imagined, just as the victim’s experience (Hudson, 2022).

(Mametz Woods (Hudson, 2022)

Reflection:

Many aspects of Hudson’s work interest me: His preparation for photographing, photographic intention, his thoughts on working in series, his philosophy and of course his images.

References:

Hudson, R. (2022) Rob Hudson. At: http://www.robhudsonlandscape.net/about (Accessed 08/09/2022).

Hudson, R. (2011) The Skirrid Hill Project: taking ‘thinking like a poet’ to its logical conclusion?. At: https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2011/04/the-skirrid-hill-project-taking-thinking-like-a-poet-to-its-logical-conclusion/ (Accessed 08/09/2022).

Hudson, R. (2016) Inside the Outside An exhibition of photography. At: https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2016/10/inside-outside-exhibition-photography/ (Accessed 08/09/2022).

STEPHEN SEAGASBY

Responds to the landscape on a physical, mental, and emotional level, using metaphor, impressionism, abstract expressionism, and his emotional response is important. He believes sequences are important and that too many questions that are left unanswered in a single image, where a group of images offers the viewer greater insight into the story or the photographer’s work.

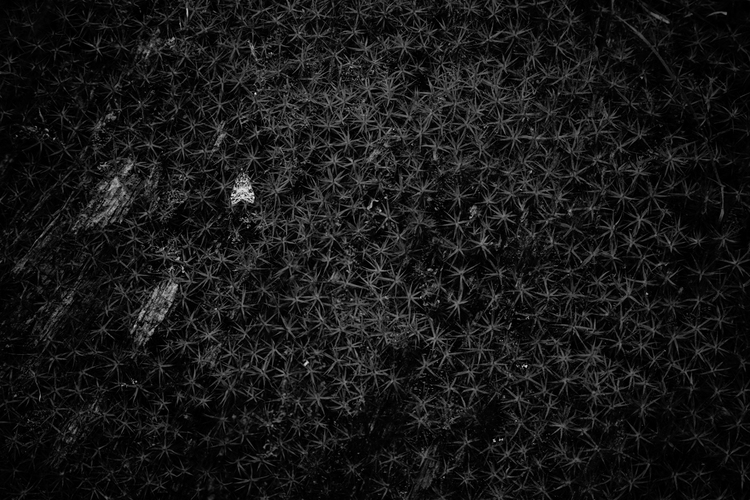

In May 2015 he spent time alone in the Forest of Dean, describing this as the most important of his work, in developing a concept and outcome that was unexpected. When he developed his films, he found most images scattered with dark shadows creeping and oozing across the landscape. The more he looked the more he “began to ‘see’ the very essence of the forest as I had perceived it” (Fotofilmic, 2016). He then printed the images quite small, to draw the viewer in for a personal experience and felt it was most successful as a group of images whilst each one has a narrative of its own.

Malevolence (ITO, 2018)

His work ‘A Process of Reclamation’ was a long-term series developed around the feeling of walking in the footsteps of those who created the slate quarries. It shows the healing of scars in a post-industrial landscape and depicts a landscape’s journey through time and the change abandonment and natural decay bring to bear. However, it also hints at the healing of our inner scars (Hudson, 2016).

Reflection:

Like Hudson he talks of the importance of value of working in a series, uses metaphor in his work, but also shows how unintended outcomes can be used for a good outcome.

References:

Colwyn, O. (2019) Inside the Outside – Out of the woods of thought. At: http://orielcolwyn.org/inside-the-outside/ (Accessed 09/09/2022).

Fotofilmic (2016) Stephen Segasby. At: https://fotofilmic.com/portfolio/stephen-segasby-kings-lynn-uk-2/ (Accessed 09/09/2022).

ITO (2018) Out of the woods of thought. At: https://www.inside-the-outside.com/publications/2018-exhibition-book/ (Accessed 30/09/2022).

Parkin, C. (2019) Stephen Segasby. At: https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/10/stephen-segasby/ (Accessed 09/09/2022).

TOM WILKINSON

Tom Wilkinson’s work explores identities of place and of self. He finds he then discovers “something about the nature of how the photograph functions within them and about the nature of the moment of experience” and gains a sense of belonging (ITO, 2016). He says that in photographing landscape you are giving an opinion of it, and so it says as much about the photographer as it does the land.

Talking of his work Nothing remains, says the work suggests the presence of an absence, of something that has been before now only seen within the present, describing it as “both visual and a philosophical enquiry into the way memory and identity function with regard to a sense of place” (Wilkinson, 2022). He says we have a consciousness of the past within the present, and therefore that if the photograph is memory, a displaced moment in time, then our sense of being-in-the-world is also this way. The series is an attempt to connect this area to the landscapes of his past and to question his identity within it.

Nothing remains (Wilkinson, 2022)

Reflection:

I like his description of the past within the present and photograph as memory displaced in time.

References:

ITO (2016) THE ITO EXHIBITION (2016) | A virtual tour and review by Tom Wilkinson Nov 6, 2016. At: https://www.inside-the-outside.com/ito-exhibition-review-tom-wilkinson/ (Accessed 09/09/2022).

Wilkinson, T (2022) Nothing Remains. At: https://anotherplacemag.tumblr.com/post/102616659632/nothing-remains-tom-wilkinson (Accessed 09/09/2022).

Wilkinson, T. (2022) Tom Wilkinson Art Photography. At: http://www.i-m.mx/tomwilkinson/ArtPhotography/about (Accessed 09/09/2022).

J M GOLDING

She uses a variety of cameras and techniques, vintage film camera, pinhole, a plastic Holga or Diana, alternating between single and multiple exposures, to explore and transform her experiences with the world. Golding describes a flow state, an almost automatic, yet highly absorbed state of consciousness, and finds, alters, and creates metaphors to share her subjective experience. She says there is “something compelling about the ways photography can be used to transform “objective” reality” and talks of transcending the literal appearances of subjects to metaphors for internal experience, and share personal meaning (Golding, 2022).

Her images have transformed reality in ways that can be quite surprising to her conscious self. In her work Before there were words, is about proverbial experience that we retain, have in our unconscious minds, and might not share through words. The photographs speak of pure actuality, that moment before verbal labels rush in to change experience (Benbow, 2016).

(Golding, 2022)

My reflection:

I was interested in the way she describes the “flow state” that she works in when self-absorbed. I can align with Golding’s photographic philosophy, particularly her description of “transcending the literal appearances of subjects to metaphors for internal experience” (Golding, 2022). Also, her view that the world illuminates what’s in our subconscious and brings it to the fore.

References:

Benbow, C. (2016) Interview with photographer J.M. Golding. At: https://www.fstopmagazine.com/blog/2016/interview-with-photographer-j-m-golding/ (Accessed 09/09/2022).

Golding, J.M. (2022) At: https://www.jmgolding.com/before-there-were-words/wigdebnrfagnyp1cf1wr96rfxg7jll (Accessed 09/09/2022).

Golding, J. M. and LensCulture (2022) Falling Through the Lens – Interview with JM Golding. At: https://www.lensculture.com/articles/jm-golding-falling-through-the-lens (Accessed 09/09/2022).